The Last Large-Size US Currency: A Ninety-Six Year Legacy

I was at an estate sale a few years ago when I first held a large-size US bill – a 1923 Silver Certificate that had spent decades in someone’s desk drawer. The size difference from modern bills was immediately striking, and I remember thinking: this feels like real money somehow. That sensation hasn’t faded. Large-size currency carries a presence that modern bills, for all their security features, simply don’t match.

What Does “Large-Size” Currency Mean?

Numbers don’t quite capture it, but here they are anyway: large-size notes measured about 7.42 by 3.13 inches compared to today’s 6.14 by 2.61 inches. Nearly an inch and a half longer, half an inch taller. Hold one next to a modern bill and the difference is obvious – these were substantial documents, not just transactional tokens.

The original size made sense for its era. During the Civil War, when paper currency became a permanent fixture, larger bills projected legitimacy and allowed for intricate anti-counterfeiting designs. The engravings on large-size notes remain some of the most beautiful work ever done on American currency.

Why the Switch Happened in 1929

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing had been running the numbers for years, and the math was compelling. Smaller notes meant approximately 35% savings on paper costs alone. With billions of notes printed annually, those savings added up to serious money.

But it wasn’t just about paper. Smaller notes meant more efficient production – more bills per sheet, faster printing, reduced labor costs. Storage and transportation became cheaper too. The timing aligned with broader modernization at the Bureau, including new high-speed presses that could handle the redesigned currency.

Probably should have mentioned this earlier – the transition wasn’t sudden. It was the result of years of planning, testing, and careful rollout designed to maintain public confidence throughout the change.

Types of Large-Size Notes

Collectors today can pursue several distinct categories, each with its own history and collecting dynamics.

Silver Certificates

These notes were literally redeemable for silver dollars at any bank. The government held physical silver backing every certificate in circulation. I find it fascinating that you could walk into a bank and exchange paper for metal – try that today. The blue seals and serial numbers mark these as Silver Certificates at a glance.

Gold Certificates

Similar concept, backed by gold instead of silver. The orange or gold-colored backs and seals make them visually distinctive. These notes were recalled in 1933 when private gold ownership was restricted, which makes surviving examples particularly desirable. Most were destroyed; the ones that survived are genuinely rare.

Federal Reserve Notes

First issued in 1914, these represent a philosophical shift – backed by commercial paper and government bonds rather than precious metals. They’re ancestors of the Federal Reserve Notes in your wallet right now. Large-size versions are relatively available, though high-grade examples from certain Federal Reserve districts carry premiums.

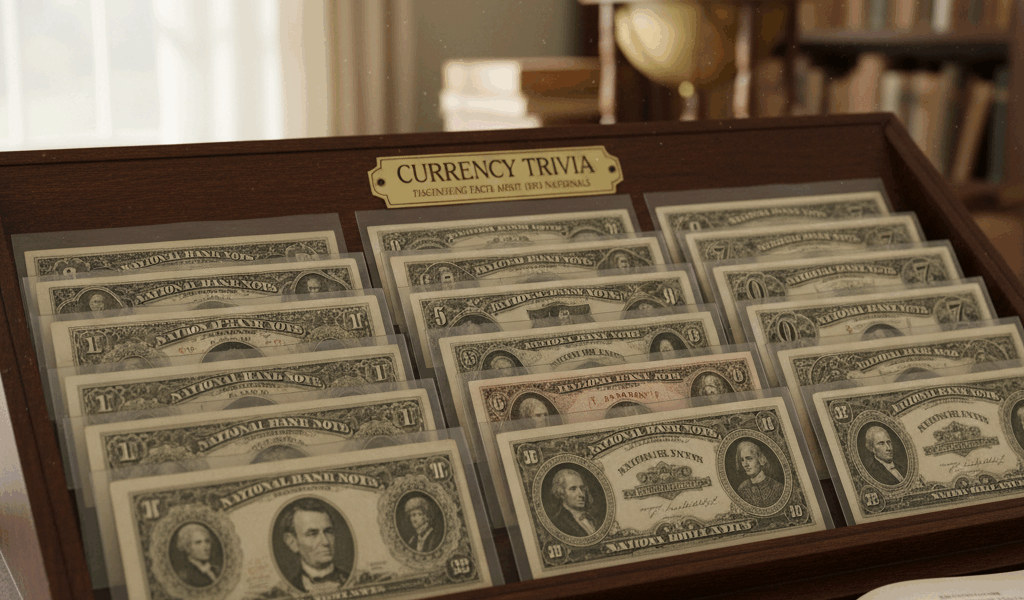

National Bank Notes

These fascinate me most. Individual chartered banks across the country issued their own notes, each bearing the bank’s name and location. This creates thousands of collectible varieties. A note from a major city bank is relatively common; one from a small-town bank that operated briefly might be extremely rare.

Collectibility and Value Ranges Today

The market for large-size currency is well-established, with clear price differentials based on type, condition, and rarity.

Common notes in circulated condition – think 1923 Silver Certificates or 1914 Federal Reserve Notes from major cities – can be found for $30 to $75. These make excellent entry points for new collectors. You’re holding genuine history for less than a nice dinner out.

Mid-range pieces typically run $100 to $500. This includes better-preserved common types, interesting serial numbers, or notes from more desirable series or districts.

Rare pieces climb into thousands or tens of thousands. National Bank Notes from small towns, high-denomination Gold Certificates, and error notes attract premium prices. I’ve watched pristine $500 and $1000 Gold Certificates sell for six figures at auction.

How to Identify and Authenticate Large-Size Notes

Start with the paper itself. Genuine large-size currency contains distinctive red and blue security fibers embedded throughout – not printed on, woven in. You can often see these fibers without magnification.

Printing quality tells a lot. Bureau of Engraving work shows crisp, sharp lines with no bleeding. The intaglio printing process creates raised ink you can feel with your fingertips – run them lightly across the surface. Counterfeits rarely achieve this tactile quality.

Serial numbers and Treasury seals should align properly with consistent color. Compare notes you’re evaluating against known genuine examples or high-resolution images from reputable auction catalogs.

For anything valuable, professional authentication pays for itself. Services like PCGS Currency or PMG encapsulate notes with grade assessments, providing confidence for buyers and sellers alike.

Building a Large-Size Collection

Most collectors start with a type set approach – one example of each major category. This provides variety while teaching the nuances of different issues. Some focus on specific denominations, seeking examples from different years and issuing authorities.

I’ve gone the National Bank Note route, focusing on notes from my home state. There’s something satisfying about connecting currency to local history, finding notes from banks that served communities my family might have known.

Whatever approach resonates with you, large-size currency offers tangible connections to American history. Each note passed through hands during the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, or the Roaring Twenties. They’re artifacts of economic and social change, compressed into pocket-sized documents that have somehow survived to reach us.