Currency as a Weapon

Civil War propaganda on currency has gotten complicated with all the revisionist takes and oversimplifications flying around. As someone who has been collecting Civil War era notes for years and studying the imagery they carried, I learned everything there is to know about how both sides weaponized their paper money to spread their messages. Today, I will share it all with you.

The Civil War wasn’t just fought with rifles and cannons on battlefields. Both the Union and the Confederacy understood something powerful — that money itself could carry messages, shape public opinion, and rally support for their cause. Paper currency became printed propaganda, persuasive arguments that circulated through every single financial transaction across the divided nation.

I’ve collected Civil War era currency for years now, and the propaganda elements still catch me off guard sometimes when I’m examining a new acquisition. These weren’t subtle designs slipped in by rogue engravers. They were deliberate, calculated statements meant to be seen and absorbed every time money changed hands. When you think about how often people handled cash in the 1860s, that’s a lot of propaganda impressions.

How Newspapers Set the Stage

Probably should have led with this section, honestly. Before we get into the currency itself, you need the context of how information warfare was already raging through print media. Newspapers were the primary propaganda vehicle of the era, and currency designers were pulling directly from that same playbook.

The New York Times and Chicago Tribune in the North published story after story emphasizing the moral imperative to end slavery and preserve the Union. Every military action, no matter how messy the reality, got framed as a noble step forward. Southern papers like the Charleston Mercury and Richmond Examiner did the exact mirror image — states’ rights, Southern honor, brave resistance to Northern aggression. Same events reported on the same days, but reading them you’d think they were describing completely different wars.

This matters for our purposes because the imagery and symbols that ended up on both nations’ currency drew from this exact same messaging playbook. None of the design choices on Civil War era notes were accidents. Every symbol was selected with intent.

What Actually Appeared on the Money

Union currency featured patriotic symbols that hammered home the national unity theme — American flags, soaring eagles, allegorical figures representing liberty and justice and the righteous cause. The messaging consistently emphasized Constitutional authority and the preservation of one nation. “E Pluribus Unum” got prominent placement on notes, which is about as on-the-nose as propaganda gets when you’re fighting to prevent your country from splitting apart.

Confederate currency went in a completely different direction, and this is where it gets really interesting to me as a collector. Images of plantation life, agricultural scenes showing prosperous Southern landscapes, and portraits of Confederate leaders all reinforced the narrative about their way of life being worth defending and dying for. State iconography appeared frequently, emphasizing the sovereignty arguments that underpinned the entire secession movement.

That’s what makes these notes endearing to us currency collectors — they’re primary source documents. When you hold one of these notes, you’re not looking at a reproduction or reading someone’s description of propaganda. You’re holding the actual propaganda in your hands, the same piece of paper that circulated through a divided nation trying to convince people of one side’s righteousness.

Illustrations and Visual Persuasion

Both sides used visual illustrations effectively because they knew a huge portion of their populations couldn’t read well or at all. Political cartoons in newspapers reached broader audiences than any editorial could, and the designers of currency followed exactly that same logic — the imagery on a banknote told its story without requiring the person holding it to be literate.

Northern caricatures portrayed Confederate leaders as foolish, incompetent, or tyrannical. Southern illustrations gave Lincoln the same treatment, depicting him as a heavy-handed tyrant and foreign aggressor. These visual languages reinforced in-group identity on both sides and dehumanized the opposition. Looking at these pieces now, you can feel the anger and fear that produced them, and that emotional charge hasn’t faded in 160 years.

The Role of Music and Posters

Recruitment posters flooded both territories alongside the currency. “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” became a Northern anthem with its powerful religious overtones and sense of absolute moral certainty — when you’re singing that God is on your side, doubt becomes pretty difficult. “Dixie” served the South in its own way, romanticizing Southern identity and framing resistance as noble and even joyful.

Soldiers carried these songs into battle and civilians sang them at home. The melodies stuck in people’s heads day and night, constantly reinforcing the ideological frameworks that justified continued fighting, continued sacrifice, continued belief that their side was right. The currency people carried in their pockets worked the same way — constant, quiet reinforcement.

Photography Changed Everything

Mathew Brady and the other Civil War photographers brought battlefield imagery to civilian eyes for the first time in history. Before this, war was something you read about or heard described. Now people were looking at haunting photographs of dead soldiers lying in fields, destroyed towns, and exhausted survivors staring blankly at the camera. The war became visceral in ways that words and illustrations simply could not match.

These photographs served propaganda purposes too, though in more complicated ways than the intentional designs on currency. Northern audiences seeing the destruction of Southern lands might feel justified and righteous in the Union cause. But those exact same images could also fuel anti-war sentiment among people horrified by the human cost. Photography was a double-edged sword, cutting both ways depending entirely on framing and context. That ambiguity is what makes the photography of this era endlessly fascinating alongside the more deliberately crafted propaganda on the currency.

Government Publications and Speeches

Lincoln’s speeches deserve special mention here. His ability to articulate Union war aims in moral and almost spiritual terms — preservation of democracy, the eventual promise of emancipation, government of the people — shaped how the entire North understood its own purpose and sacrifice. The Gettysburg Address distilled breathtakingly complex political realities into ideas accessible enough for every citizen to carry in their heart. That’s propaganda at its most elevated and effective.

Jefferson Davis made similar efforts on behalf of the Confederacy, framing secession consistently in terms of Constitutional rights and self-determination rather than slavery specifically. Government publications on both sides echoed their respective leaders’ themes, creating a propaganda ecosystem that reinforced itself at every level — from presidential speeches to newspaper editorials to the very money people used to buy bread.

Why This Matters for Collectors

Civil War currency carries all of this history embedded in every fiber of the paper. The design choices, the iconography, the messaging — it’s all there, frozen in time on every note. Collectors aren’t just acquiring interesting-looking pieces of old paper. They’re preserving primary documents from one of the most significant, painful, and transformative periods in American history.

Understanding the propaganda context behind these notes helps with attribution and accurate valuation too, which is a practical benefit on top of the historical one. Rare variants often exist precisely because specific messaging didn’t work as intended, or because circumstances changed mid-production run and the designs had to be adjusted. The stories behind why certain notes look the way they do matter — for your understanding, for your collection’s value, and for keeping this important history accessible to future generations.

Recommended Collecting Supplies

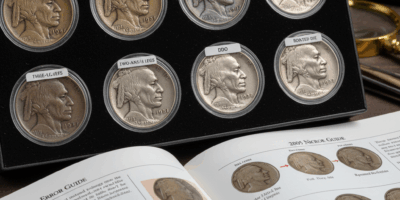

Coin Collection Book Holder Album – $9.99

312 pockets for coins of all sizes.

20x Magnifier Jewelry Loupe – $13.99

Essential tool for examining coins and stamps.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.